Chapter 1

Rose

Lake Patrizio

1742 A.D.

As the moss-hung canopy of the bayuk gave way to the open sky of Lake Patrizio, Rose Bainbridge picked up her paddle and began paddling. Stroke left, stroke right. Stroke left, stroke right. She kept her rhythm steady, matching the speed of the pirogue as the small boat moved across the surface of the water toward the rusted and smokestained skyline of New Venezia. Force of habit driving pointless precision, she thought. Because she rowed only to preserve the illusion that rowing was necessary, to hide the truth that the boat moved across the water at the will of the pirogue’s other passenger.

Continuing the pantomime of rowing, Rose looked over her shoulder at Chal. The native girl sat in the stern, her paddle in the bottom of the boat, untouched, her long black hair loose and streaming behind her in the wind of their passage. Chal saw Rose look at her, and used a finger to push stray wisps of hair out of her face and tuck it behind her ear.

“Maybe we’re going too fast?” Rose said.

That made Chal laugh, a sound like water over rocks. The speed of the pirogue increased.

Forcing her lips into a line to prevent a smile, Rose faced forward again. She resisted the temptation to row faster, because that would only encourage Chal further. Sometimes the girl could be such a … a … little girl. Not for the first time, Rose wondered if this was what it was like to be a parent. And not for the first time, she regretted the thought. Because she would never know.

You ever seen a pregnant gunwitch?

The question rose from the past to mock her again.

Rose gritted her teeth and stopped that line of thought. Now was not the time. What was done was done.

The pirogue went faster. The rushing water nearly pulled the oar out of Rose’s hand.

She gave up on rowing, braced the oar on the bow in front of her and looked back at Chal again. The wind whipped loose strands of Rose’s hair across her face and pulled against the metal clasp that held back the rest.

Chal met her gaze and laughed.

In spite of herself, in spite of bad memories, in spite of the unexpected and unwelcome summons from General Tendring, Rose laughed as well. She could not say precisely why she laughed. Whatever the reason, the laughter was a welcome release. Even if it lasted only seconds.

As her laughter subsided, the pirogue settled into the water again, its speed diminishing.

Rose faced forward again and resumed her needless rowing. “I’m just trying to protect you,” she said with a quick look back over her shoulder.

Chal’s teeth flashed in a smile. “And I you,” the girl said. “The waters move the boat, so you row to hide what they do. The storm clouds follow you. So I help you outrun them.”

“Some storms you can’t outrun,” Rose said.

Chal’s smile turned rueful, and her apparent age matured, the little girl gone. Rose did not know how old Chal was. In their five years together, companions in the bayuk, scouts leading and protecting ambitious colonists to the frontier, the girl would never give a straight answer to the question. “I am a child among the children of the world,” Chal would say. Or, “I am not so old that I cannot dance in the rain.” Mostly, though, Chal would only laugh that bubbling laugh of hers and look mischievous and even younger. Rose judged the girl to be no more than twenty, maybe as old twenty-five. Maybe young enough to be Rose’s daughter. If Chal had been born half a world away. If …

Rose turned to face forward again.

Behind her, Chal sighed. “The storm clouds still follow.”

Rose did not reply. She focused on keeping her rowing steady. Left, right. Left, right. Focus. Concentrate. Repeat. The mantra from her instructors. In repetition there is concentration. In concentration there is focus. In focus there is power.

In focus there was no memory. No lost child. No lost innocence. Only the oar in her hands, the water of the lake, and the companionship of Chal.

With focus, though, also came increased sensitivity. Now, when her paddle dipped into the water, Rose could feel the subtle shiftings that created the improbable current that pushed the pirogue along. Magic, not unlike her own, but she did not know how Chal did it. The subtlety of the moving current belied the power invoked.

With her pistol, Rose could make a man explode at five hundred yards, further if she had a scope and properly measured powder. Then she could do a right-face and engulf a small building in flame or rip out its supporting walls. But all of that seemed insignificant to what Chal did so easily from the back of the pirogue, directing the currents of a lake the size of Lake Patrizio. Rose needed concentration and her pistol. Chal seemed to need only a laugh and a whim.

More than once Rose had speculated on how she might move the waters the way Chal did. At first you do not know what you can do. Then you know. Then you do. More words from her training. The corporals at the King’s Coven did not teach the conscripted privates of the 101st Pistoleers. Rather, the corporals demonstrated what was possible, sometimes on the privates, then insisted that the privates duplicate their results. But in this Rose had chosen not to know or to do. She knew and had done much that she wished she could forget and undo. She would not pry into Chal’s native secrets. She preferred the mystery. She had not asked Chal who or what the native girl was running from, hiding from. And Chal had never asked her the same questions.

The lake water, so blue after the murk of the bayuk, became dirty again as they neared the city, but dirty in a way very different from the shallow streams of the bayuk. Here sunlight gleamed a rainbow along the oily surface and highlighted floating trash and debris. Other boats, pirogue’s like theirs, as well as rafts and barges and fishing boats with sails or outboard paddles and belching smokestacks spread from the city’s lakeside docks and piers.

Rose maintained her pretense of rowing as Chal threaded a path through the other boat traffic. She only stopped when they approached an open berth on a mostly empty pier. A few other pirogues had been tied up to the pier, and a dilapidated barge was being unloaded. She stepped out of the boat to the dock and tied off. She looked around as she pulled her pistol from her belt to check its load.

None of the laborers or slaves unloading the barge paid her or Chal any mind. But the big foreman barking orders in a mixture of German and English paused midcurse to stare at her.

Rose returned the man’s stare, blank expression in response to leer, then inspected her pistol. Satisfied that the load and the priming were still dry, she pushed the runecarved muzzle into her belt again and turned her back on the foreman. In the pirogue, Chal picked up Rose’s rifle and tossed it up to her. Rose caught the rifle with both hands and automatically checked its load. Also still dry. She adjusted the strap so the stock would not hit her legs as she walked, then slung the rifle over her shoulder. Trained and disciplined as an infantryman in the King’s Army, Rose had often wished she was as tall as one, as well.

“Well well well.” A man’s voice, thick with a German accent. “What is this? A couple of savage beauties?”

Rose turned around. And looked up. The foreman was even bigger up close. She smiled and put her hand nonchalantly on the butt of her pistol. Then dropped the smile and pulled out the gun. The foreman was not looking at her. No need to be subtle if he was watching Chal.

“Madchen!” he shouted over Rose. “Be careful. You will tip it–”

He watched in shock as Chal walked down the center of the pirogue, then leaped to the dock. Rose did not have to look to know the boat had scarcely shifted. And had certainly not tipped over. Chal refused to go into water, whether river or lake–and never the ocean–not even up to her ankles, but boats on those waters did what Chal told them. Even without the boat, though, Chal turned men’s heads, drew their attention away from more pressing dangers.

Rose stepped up to the man and poked him in the ribs with the muzzle of her pistol. She did not bother pulling back the hammer. She hoped he would just back off and let them go. It was already hard enough to get work in New Venezia. Men had a difficult time hiring a woman who could–and had, in front of multiple witnesses–beat a man senseless with just the butt of her gun, her bare hands, and a pair of dirty moccasins. She doubted the foreman was looking to hire a scout to guide his barge through the bayuk, but people would talk. And, judging by the size of him, she was not sure she could take him alone. She was an inch or two taller than the rifle she carried, but he was another twelve inches taller still. And at least three stone heavier. At least.

The pistol pulled the man’s attention from Chal. He looked down at Rose. “Now now now,” he said, backing up, “there is no reason to being hasty.”

Rose stayed close, moving with him as he stepped away, keeping the pistol pressed against him but letting it slip down until the muzzle rested against the man’s heavy belt buckle. Now she cocked it. The man’s face went pale and he stepped back again, this time trying to twist away. Rose still followed him, pushing the muzzle hard into his stomach, forcing him further back until he teetered on the edge of the wooden platform over a short drop to the water. “We’re in a hurry,” she said. “Versteht?”

“Ich–I–yes.” His eyes moved from her to behind her, then back to her.

Rose nodded and resisted the urge to push him off the dock. She turned her back on him. As she expected, Chal stood to one side, cradling her short-barreled cavalry rifle, stock in the crook of her right arm, hand resting near the trigger, barrel only coincidentally pointing at the center of the big man’s chest.

Chal smiled at her and Rose smiled back.

“Hunde!” he yelled at them from behind as they walked away.

* * *

Rose and Chal walked along the pier and through the busy docks, ignoring the catcalls of the laborers and the sullen glares of the slaves. They stepped around the steamgrunzers that loaded and unloaded the larger seagoing merchant vessels and filled the air with the white hiss of steam, the black smoke of burning coal, and the clank-thump-clank-thump of heavy gears and metal feet.

They walked through the lakefront quarter of the city, where the wooden structures of the original natives and first wave of Italian settlers still predominated, though under the looming shadows of steel and concrete put up by the German and, more recently, English trading companies. They pushed through the crowds of sailors, soldiers, rivermen, colonials, and natives to reach the wide street that led to the front gate of Fort Gunter.

In the heart of New Venezia, away from the docks, two more women generated little notice. Even one with a long rifle and another with the high cheekbones and smooth dark skin of a native queen. The crowds thinned as they neared the fort, though, and they stood out again, two women entering the world of men.

On a flat parcel of cleared ground before the fort’s main gate, a line of wargrunzers stood awaiting maintenance, idle, with only thin steams of black smoke leaking from their high-mounted smokestacks. A group of mechanics had removed the arms from the first wargrunzer, and were reboring the cannon arm and recalibrating the loader arm. The torso stood near the mechanics, a temporary double amputee but still standing more than twice as tall as the tallest mechanic. Unlike the other grunzers, who seemed to be inactive, the head of the grunzer being serviced turned back and forth with a clicking of gears, looking first at the mechanics, then at the other side of the field. Once it looked at Rose and Chal, then turned its blank “face” back to more immediate matters.

Across the field from the wargrunzers and the mechanics, sergeants and corporals drilled colonial conscripts and volunteers under the watchful eyes of a leftenant.

“Company halt!”

“Left face!”

Rose felt her muscles flexing, remembering the responses to the shouted commands.

“Present arms!”

On a whim, Rose stopped resisting and brought her rifle around and held it in front of her. She adjusted her step and her pace to match the cadence of the callers. She saw that she had drawn the attention of a few recruits.

“Shoulder arms!”

She shouldered her rifle and kept marching. Out of the side of her eye, she saw Chal beside her standing straight, balancing her carbine on her shoulder, parodying Rose’s high marching step. And she could see that even more of the recruits had noticed them. Or noticed Chal, at least. So had the leftenant. He leaned over to the master sergeant and gave instructions.

“Right face!” bellowed the sergeant.

In ragged lines the recruits turned their backs on the women. The leftenant scowled at Rose and Chal, then turned his back on them as well.

* * *

Rose, rifle again slung over her shoulder, presented herself to the sergeant on duty. “Rose Bainbridge,” she said. She resisted the urge to give him a salute. “Scout,” she added. She pulled the folded summons out of her blouse and handed it to him. “Here at the request of General Tendring.”

The sergeant took in Rose, her worn cotton and buckskin clothes, and her similarly attired native companion, and managed to express extreme annoyance and displeasure, all without moving a muscle on his lined face. Then his eyes landed on the regimental badge bent into a bracer on Rose’s right arm. The metalwork tracery, once bright red, was now faded with age and soiled with sweat and dried blood, but the badge still plainly showed the crossed musket and lightning bolt of the 101st Pistoleers. The sergeant raised one eyebrow, ever so slightly.

“Right,” he said. Then looked away and muttered, “Bloody witches reunion.”

“What was that?” she asked. Then added, “Sergeant?”

The sergeant turned back to her, met her eyes. “Private Donalsonne will take you to the General,” he said. Then added, “Mum.”

A man who had been standing against the wall behind the sergeant snapped to attention and came over. He saluted the sergeant, then turned to Rose and Chal. “If you will follow me, please, Mum.”

Rose held the sergeant’s gaze for a few seconds more, but she learned nothing from his gray eyes. She indicated to the private to lead on. A witches reunion? The King kept the 101st Pistoleers, what the rest of the army called “the gunwitches” or just “witches”–and sometimes, usually out of earshot, “the bitches crew”–in England, though sometimes the small groups of gunwitches were detached to the Continent. But never to the Colonies. At least, not while they still wore the uniform. Rose put her hand on the butt of her pistol. Beside her, she felt Chal pick up on her new tension.

She and Chal walked side by side behind the private. The private did not look back.

Around them, men in red uniforms went about the duties of the fort. The men noticed the women, of course. Military discipline, and proximity of officers, kept the catcalls at an almost subvocal level. Still, men would nudge their comrades and indicate Rose and Chal with nods of their heads or even outright pointing. Only a few noticed Rose’s regimental badge. But those who did, she knew, spread the word. No catcalls from those men. Just furtive whispers of “gunwitch”. And those who heard the whispers stopped leering. Some turned away, crossing themselves. Some spit into the dirt. But none of the men they passed acted as if they had seen another woman from the 101st.

Rose ignored the insults, just as she ignored the catcalls.

A reunion meant more than one. More than just her. In his summons, though, General Tendring had not mentioned another gunwitch. How many of the 101st had she ever heard had been brought to the New World? Five? Six? Of those, Rose was the only enlisted. And of those, only three had come over in the last nine years.

Who could it be, the other gunwitch? Or gunwitches. It had to be someone like her, who had been dishonorably discharged and transported in lieu of execution. Witches had not been burned at the stake in Jolly Olde England for more than seventy years. But neither a renegade witch, nor an uncooperative–or no longer cooperative–gunwitch of the 101st would be allowed to run free. And it was impossible to hold them in prison. A gunwitch who did not want to be held was very difficult to hold. That did not leave many options. Specifically, it left two. Beheading or transporting.

General Tendring had been a Colonel when he commuted the sentence of Master Sergeant Rosalind Bainbridge. Usually only officers were transported, out of deference to their rank, not mere sergeants. The colonel had spared her from the headsman after her defiance and revolt only because she had saved his life at the Battle of the Seine outside Paris.

Rose tried to relax her grip on her pistol, but her fingers would not cooperate. Not since she had stepped on the deck of the boat that transported her to the Colonies, and then had walked off that boat and into the bayuk had she felt like this. She was scared–but this time scared of what she knew, not the unknown wilds of the Colonies–and the gun was the only comfort available.

Private Donalsonne led them up a narrow external stairway and to a deck that overlooked the interior of the fort. For the first time since he had turned his back on them at the gate, he faced them. His eyes darted to Rose’s hand on her pistol. Rose did not need to look to know that her knuckles showed white. She kept her face blank. It was all she could do not to pull out the pistol, to have it ready.

Because maybe the other gunwitch was not a woman.

“If you will wait here,” Private Donalsonne said, “I’ll announce you to the General.”

Rose nodded and the private spun on his heel. He went to one of the doors that opened off the deck.

Ducoed? No. Thomas Ducoed hated the army more than she did. She had heard that he managed to receive a commission and then an honorable discharge. She wondered how he had done that, but knew she would not like to hear the details. He had come to the Colonies four years ago and lived for a while in New Venezia. Rose had avoided the city while she heard he was there. Then he had disappeared into bayuk and bush. She had hoped he had died. She had imagined his gruesome death more than once.

The private returned a minute later and held the door. “The General will see you now.”

Before Rose could move to the door, though, an officer stepped out and looked at both Rose and Chal. A young man, hardly older than Chal, but a major by his insignia. He walked to Rose and extended his hand. “Sergeant Bainbridge,” he said. “It is indeed a pleasure to meet you.”

Unsure how to respond, Rose took her hand off her gun and held it out in front of her. He shook her hand, his grip firm and warm.

“I have heard so much about you,” he went on, the corners of his mouth tugged slightly by a smile that also shone in his green eyes. “I could scarcely believe when the General told me you had been summoned. Forgive me,” he added. “I am Major Ian Haley of His Majesty’s Army.” His grip shifted and he gave her an elaborate bow, then kissed her hand.

Rose felt her face growing warm under his attention, and noticed that he still held her hand. She took the hand back and said, “Please, Major, just Rose. I was stripped–” Her tongue twisted after she said the word, both from the remembered humiliation of the day, and from the intensity in his face as he looked her. If she had been suddenly stripped for real, disrobed in front of this handsome young man, she could not have been more flustered. “Just Rose,” she repeated, shortly. Only a bit more shortly than she intended. She turned slightly, to deflect his attention. “And this is Chal. My friend and companion. She is a native from across the Gulf.”

If he heard her tone, the Major’s face did not show it. He gave Chal a short bow, then turned back to Rose. “A pleasure to meet you both,” he said. “Rose. And Chal.” He gestured toward the door where Private Donalsonne still stood at attention. “If you will precede me, the General is waiting. And so are some other people who are most eager to meet you.”

The room she stepped into seemed dark after the bright morning sun, despite the windows and the fire in the hearth. The others in the room were silhouettes standing around a table in the center of the room.

One of the silhouettes, tall, a man, with unruly curls turned to face her. She did not need to see him clearly to recognize him. In the gloom, his blue eyes were dark gray, his brown hair almost black. But his lips, pulled into a smirking grin, showed a smile she had never been able to forget.

She had her pistol out of her belt and level, hammer back, pointing at his heart in less than a breath.

“Rosalind,” Ducoed said. Behind him, across the table, Rose heard surprised intakes of breath and a girlish whimper. Behind her she thought she heard the major grunt in surprise.

Rose bared her teeth. “Don’t say my name.” Her voice, like her gun, rock steady.

“Then what should I call you?”

“What is the meaning of this?” The General’s voice cut off her reply. The General stepped forward, to Ducoed’s left. “Sergeant Bainbridge, if you have a grievance with your former comrade-at-arms, I would appreciate it if you settled it outside my quarters. And,” he added, looking past Rose, over her shoulder, “whatever that complaint might be, I can not imagine that it involves my newest officer.”

Rose did not take her eyes off of Ducoed. “Chal?”

“The handsome major is covered, yes.”

Rose risked a quick look back. Chal had her carbine positioned under Major Haley’s chin, and him on tiptoes, hands wide and high.

Ducoed shifted to his left, toward the General, trying to use her momentary distraction. But Rose followed him, grabbing his shirt with her free hand, pulling him to her, pressing the gun against his chest. Ducoed opened his mouth.

Rose’s fingers tightened on the trigger.

“Sergeant Bainbridge,” the General said, his voice sharp, commanding, but not loud. “I must insist that you put your gun away. And tell your companion to stop threatening Major Haley.”

Rose looked into Ducoed’s eyes, and he looked back, closing his mouth. The smirk faded from his lips until his face was a mask of indifference. His eyes told her nothing. She tried to look deeper, into whatever was left of Ducoed’s soul, looking for whatever might be left of her friend. She looked for something, anything, and he gave her nothing. She could not penetrate below the surface of the man her friend had become. Then she felt foolish for even trying. Her friend had been gone for twenty-five years. That was why Ducoed angered her so much. He owed her so much, yet never acknowledged even the tiniest debt. He only caused pain. He never felt it.

She wanted to kill him, where he stood, so close that she would feel him die. Let hot lead and cold magic rip him to pieces. Maybe he would feel that. Maybe then he would feel her pain. She could do it. She had done worse.

But not since she had left the army. Here she was, though, standing inside a fort again, gun ready, ready to kill with officers looking on.

“Sergeant Bainbridge?” The general’s voice was almost gentle.

Movement behind Ducoed caught Rose’s eye, and she saw two girls holding each other and looking at her with terror. The sight of those pale, young faces, so out of place in the fort, so afraid of what she might do, achieved what the general could not. Had she looked like these girls twenty-five years ago? Was she fulfilling the role for them that the army and Ducoed had assumed for her? Whatever else she might do, whatever else she might be capable of, she would not do that.

She let go of Ducoed, pushing him away as she stepped back. She did not want to–she would not–kill him in front of the girls. For one last instant, though, she hoped he would make a move, any move, even the twitch of a hand. But he only stood there, and looked at her.

She released the hammer on the pistol and settled it back in place. Then she pushed the gun into her belt again. Behind her, she heard the major’s heels come down on the floor and Chal appeared beside her.

“My apologies, general,” Rose said.

* * *

The general had chairs brought so everyone could sit down, then had a private serve tea.

“I’m not accustomed to such displays in my briefing room,” he said, looking over his cup of tea at Rose. Rose met his gaze, but said nothing. “Though perhaps,” he went on, “there is a lesson to be learned. Wouldn’t you say so, Major Haley?”

“Yes, sir,” the Major said.

“Young and pretty does not mean helpless.”

Major Haley’s face colored and he dropped his eyes to his tea. “Yes, sir.”

General Tendring turned to look at the oldest of the girls. “Isn’t that right, Janett?” The girl looked pleased. “I am not accustomed to such displays of emotion. However, as I have now lived through several of them, two just today, perhaps it is my expectations that should change.” Now the girl’s face flushed. “There is no excuse, though, for my own lapses. I have been remiss. Sergeant Bainbridge, may I introduce to you Janett and Margaret Laxton. You have already met their young protector, Major Haley. And of course you know Leftenant Ducoed.”

Rose bowed in her seat toward the two girls and gave the major a nod and an apologetic smile. She did not look at Ducoed.

Janett rose from her chair when introduced and gave a perfect curtsy. Margaret did the same, but without grace. Standing too quickly, then sitting too loudly. Margaret met Rose’s eyes, then looked away. Janett was the older of the two girls, very pretty, with auburn hair and blue eyes. Rose guessed her age at seventeen or eighteen. Margaret, she decided, could not be older than thirteen. Unlike Janett’s impressive coiffure, Margaret’s blonde hair looked as if it had been only partially tamed, and her arms and legs seemed too long for her dress. Her blue eyes, though, were an exact match for Janett’s. And they stirred long dormant memories.

“You are acquainted with their father, I’ve been told,” the general said. “Colonel Laxton. Though the Colonel was only a Leftenant when you knew him.”

Rose kept her expression neutral. “Yes, of course. I remember Leftenant Laxton.” She heard Ducoed’s low chuckle, and it sent a chill down her spine along with the remembered pain of punishment. Yes, they were both acquainted with the former Leftenant Laxton. She noticed Margaret looking at her. But when Rose turned to face the girl, Margaret looked away and would not meet her eyes again.

“Good. Because you’re going to take the girls to see their father. At Fort Russell.”

Rose leaned forward in her seat. “Isn’t it traditional to ask first, general? I’m not in the army anymore.”

General Tendring put his cup down on its saucer. “I have been assured that you would be accompanying the girls. Though, after your recent display,” he added, looking at Ducoed, “perhaps those assurances were given prematurely.”

“He said I would go along?” She pointed at Ducoed, but her eyes never left the general.

“And I remain convinced,” Ducoed said, speaking up for the first time, “that Sergeant Bainbridge will agree to come along with me and the girls.”

“I will be along, as well,” Major Haley said.

“Yes, of course,” Ducoed replied.

Rose ignored both men. “Taking these girls upriver? Are you all mad? There’s a war on.”

The general nodded. “Yes, there is a war on. And it is possible that we’re all mad, as well. Hear me out,” he said, holding up a hand to forestall Rose. “As Janett has pointed out to me many, many times over the past weeks of her stay, the war has not come so far south as Fort Russell. Not yet, in any case. And her father is expecting the two of them to visit. After a journey so far across the Atlantic to reach here, the girls refuse to be so close and not seize the chance to see their father.”

“Forgive me, general,” Rose said, “but I have to ask. What has this to do with me?”

“We simply must go see our father,” Janett said.

“He’s waiting for us,” Margaret said.

Rose looked at Margaret. Those were the only words she had heard the girl say so far. Margaret met her eye, but only for an instant, then looked away. Rose turned back to Tendring.

“As you have said,” the general went on, “there is the war to consider. Though the main thrust of that war is happening far from the Gulf of Azteka, its tendrils have reached even here. Two days ago, I dispatched reinforcements upriver to Fort Russell. As you can see, and as I have heard at every pause, I did not send the girls with those reinforcements. This was for several reasons. Foremost among them, young ladies such as Janett and Margaret have no place on a march with men-at-arms. Secondly, the river has become too risky for them to travel. The way is too open, too obvious.”

“So you’re going to send them through the bayuk with this man?” She pointed at Ducoed again.

“Leftenant Ducoed served with distinction for twenty years,” the general said, a slight edge in his voice, “and he was discharged with honor.”

Rose looked away from the general, and away from Ducoed. She knew all about Ducoed’s honor. And the general knew all too much about her own dishonor.

“The Leftenant presented himself at the fort nearly a month ago, offering his services as a scout. At his request, I kept the nature of his past service confidential–”

“Of course,” Rose interjected. The enlisted men would trust a gunlock even less than a gunwitch. At least a gunwitch could be recognized immediately. Only one type of woman wore a uniform in the King’s Army.

General Tendring ignored her. “When the girls arrived in New Venezia, my first thought was to ship them straight back to England. But they prevailed upon me. Twice, I must confess. First, to stay, and now to see them escorted into the arms of their waiting father. Hearing their story, Leftenant Ducoed volunteered to assist them.”

“But, General–”

“Please, Sergeant Bainbridge. Allow me to restate myself and make up for my earlier mistakes. You are correct. You are no longer a man-at-arms subject to the King’s officers, and I was wrong to presume to give you orders.” He paused. “Will you accept my apologies, Rose Bainbridge?”

Rose could not keep the surprise off her face. The general had never called her by her name. Not once in all their years together. Being officer and enlisted in the King’s Army there could be no familiarity. Even as they huddled in the cold, hiding from the Hexen, two isolated English survivors of a campaign gone horribly wrong.

“Please,” Rose said, dropping her eyes. “Don’t think of it.”

“Rose Bainbridge.” The repetition of her name brought her eyes back to his. “Would you offer this assistance to your King, and to me, and see to the safe delivery of Janett and Margaret Laxton to their father, Colonel Laxton, at Fort Russell?”

Rose wanted to say No. She almost said it. Then she saw Margaret looking at her, face open and eager. The little girl even met Rose’s eyes, faltering only an instant. The general had said her name, and he had asked her. Asked her. Old loyalties stirred and quarreled in her chest.

She did not want to accept. Not yet. “Does he have to go?” she asked, pointing at Ducoed.

The general steepled his hands and looked at her. “You have both served me well in the past. I have no doubt that you will both serve me well in this. And I can think of no safer way to send the girls than in the company of two members of the 101st Pistoleers.”

Rose could think of many, but she realized that the general would not agree. Damn Ducoed and his distinguished service and honorable discharge.

“And he–” she pointed at Ducoed again, still refusing to look at him–“requested that I be a part of … of this?”

General Tendring shook his head. “No, the Leftenant was surprised to discover that I knew of your whereabouts, and that you were so near at hand. Or were, last I had heard. I suggested that you might need …” He paused. “That you might be willing to assist, and Leftenant Ducoed agreed immediately. He assured me that when you knew the full nature of my request that you would not hesitate to offer your gun and your knowledge of the bayuk. So I sent for you.”

Rose kept her face impassive and resisted the urge to take a deep breath and let it out slowly. She looked at the general, then at Janett and Margaret. “Right.” Bloody hell, was what she wanted to say. She would not denounce Ducoed. She never had, despite what he had done. But she would not let him take the girls through the bayuk by himself. She said, “I’ll do it. But only as a civilian. I’m not rejoining the Army.”

“Thank you thank you thank you,” Margaret said, bouncing in her seat.

Janett gave her a smiling nod. “Thank you, Miss Bainbridge.”

The general also gave her a nod, his face as impassive as Rose’s.

“I knew you would,” Ducoed said.

Rose refused to look at him. If she looked at him, if she saw his smirk, she was not sure she would not shoot him, right there in front of the general and the girls, consequences be damned. “You don’t know me,” she said. “Not at all.”

* * *

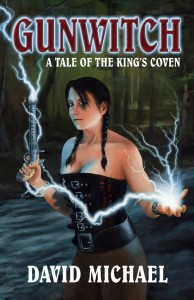

Longer samples of Gunwitch: A Tale of the King’s Coven are available for Amazon Kindle, Barnes & Noble Nook, and from Smashwords.

|

|

|